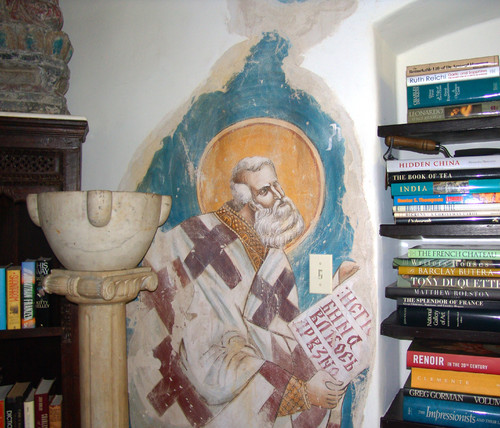

Byzantine Fresco Installation – true (buon) fresco, by iLia Fresco (Anossov), Hollywood CA, 2011

Like the traveler in H.G. Wells “The Time machine,” I recently had the opportunity to transport myself through time. Though he went to the future and I went toward the past, my journey had the advantage of occupying both spheres at once. I was a voyeur watching the artists in the caves of Lascaux, Michelangelo crouching under the Sistine ceiling on his scaffold, Raphael in the Vatican, and a side trip to Pompeii thrown in for no added cost.

My ticket for this eye-opening voyage was an invitation to watch iLia Anossov paint a buon fresco on the wall of a landmark Hollywood residence. Not just a fresco, but a “buon fresco,” or true fresco, the classic technique that’s centuries old, virtually indestructible, and au courant in its ecological purity.

Fresco is painting on wet plaster, quickly. Or so I thought from years of sightseeing and art history lectures. Shamefully, though I’m an oil painter and experienced with most painting media, and more embarrassing, the creator of several large wall murals in acrylic, I had clearly remained ignorant why fresco is referred to as “the mother of all arts.” Its depth and shadow is created through the use of what is called an underpainting, of tonal values. The old masters in oil laid glaze upon transparent glaze over this, resulting in a rich depth and surface often missing from modern work. And although I’d used this technique for years, I’d never realized it was the basis for fresco. A master fresco artist’s extensive knowledge of materials and techniques divides the master artist from the pretender, and as with myself, unaware professional as clearly as a child’s drawing of a house from an architectural rendering.

While I knew “painted on wet plaster” and had been within feet of several famous works, it somehow had escaped me that fresco was a thin media, most similar to watercolor, and that much of the drama in the technique comes from what lies in the shadows, from the initial layer of “verdaccio,” the watery mixture of black and ochre. A large work on a wall or ceiling must be readable from close and far, thus the visual cues include some trickery, or trompe l’oeil.

When I arrived at the fresco site, the base layer of plaster, or “arriccio,” for the first day’s work (or “giornata,” a daily painting section), had been laid onto the existing wall the day before. The smoother, whiter top layer, or intonacco, was now ready for the colors. I watched iLia (or The artist) transfer his full size drawing, or “cartoon” onto this layer of damp plaster, carefully lining up the squared grid. All information for lights and darks had been carefully drawn into the original copy of his cartoon; there’s no time to make these decisions while working. When the plaster is too dry to properly accept the paints, the artist must be finished, no small challenge to modern artists that are used to manipulating their media and editing.

The first giornata was at the top of the wall, about 20 feet up, in the corner of a stairwell. The scaffold itself reminded me of reading translated letters from Michelangelo to a friend, complaining of being doubled up in a squatting position and painfully painting over his head for the Sistine ceiling. Because, like Michelangelo, iLia couldn’t step back to view his work, he had to be aware of how his brushstrokes and choice of colors and shadows would look when dry from both near and across the room. Buon, or classic fresco isn’t something the artist can come back and touch up when dry because the surface will be glaringly different.

Byzantine Fresco Installation (detail – Saint by the Stairs) – true (buon) fresco, by iLia Fresco (Anossov), Hollywood CA, 2011

You would think this would lead to a frenzy of paint application, but in fact iLia is notably methodical and steady. He builds up the layers and as they dry, adds more layers of the same or different color to provide depth and detail. Often the section appeared finished to my untrained eye, but after several more steps, the effect was far more interesting and complex. Multiple layers of color may be applied with an opposing brushstroke that is interesting up close and provides a more pronounced overall effect from a distance.

The first and some say the most important painting step in fresco is applying the verdaccio, or tonal values, a mixture of black and ochre mineral pigments thinned, as are all colors, to the consistency of water. It is applied in a smooth stroke or with various styles unique to the artist. Much of this layer has been left visible by Michelangelo, if you look at close up photographs of the Sistine. Perhaps the best description of this technique would be to say it’s like looking at a black and white version of the final painting. Daunting to beginning fresco artists is the fact that once laid down, the shadow can’t be removed, the plaster owns it.

Several small pots of colors, each mixed in the studio earlier with lime putty and the ground mineral colors, were ready to use. Technically speaking, the plaster and mineral colors don’t dry, but undergo a chemical reaction when calcium carbonate is formed as a result of carbon dioxide from the air combining with the calcium hydrate in the marble. Literally a piece of quarried marble that has been finely ground and mixed with water and has an aggregate such as sand added. Fresco is, in fact, “painting with molten marble.” The limestone caves of Lascaux provided a natural example of this alchemy, the reason they are still clear after millennium. The painting itself requires high skill, but without the proper preparation and high quality minerals, a fresco isn’t going to last or have the quality that we associate with this style of painting. “Secco” fresco, painting on dry plaster, or faux painting with synthetics, will never esthetically approach the surface or color quality of a buon fresco whether on a small tile or entire wall.

The frescoes being created by iLia over several days were eventually going to have the appearance of ancient fragments, as if the entire wall had been a fresco and only these sections remained. This is an innovative, contemporary application of fresco that provides a far more interesting piece of artwork on a wall than a painting. Today’s giornata was an angel complete with golden halo, a classic image. The fresco could as easily have been a Cubist design or pure color area, but in this landmark property with heavy wooden ceiling beams, arched windows and ornate stone fireplace, religious classicism was the owner’s elegant choice.

Byzantine Fresco Installation (detail – Virgin) – true (buon) fresco, by iLia Fresco (Anossov), Hollywood CA, 2011

After the verdaccio, an intense blue sky was applied in flowing brushstrokes. The paint was absorbed immediately, and lightened within a few minutes. Fresco imparts an economy of painting to the artist because the materials don’t allowing a second choice or “fixing,” only enhancement. Watching iLia construct the face was a lesson in the essence of portrait painting. Modeling the features, the colors would seemingly disappear into the whole, yet every moment the face became more lifelike and three-dimensional. Cross-hatching small strokes with various layers of colors, broad curls of burnt sienna hair and highlights, details within the eyes, took about an hour and gave the figure an importance that would carry across the room yet not knock you off the stairs when viewing it from the closer second story. Next, the clothing, which illustrated the effective use of verdaccio tonal values within a white robe, requiring only spare strokes of a subtle red madder with some highlighting white to create the texture of soft and flowing cloth.

In classical painting before the Impressionists, transparent oil and egg glazes were applied to achieve this same depth. What was not recognizable to me from years of lazy tourism or not having heard it in the first place from painting instructors, is that fresco paint is mostly transparent. Most of us look at modern murals and faux finishes and think that fresco is the same technique. It’s not called the “mother of all arts” for nothing; earth minerals are as basic to color production as the mother is to the baby. One of painting’s first developments was the addition of egg yolk for adhesion and transparency to alleviate the flatness and impermanence of color and water. As more complex oil mediums were discovered, the simplicity and formulas of the earth’s marble and mineral mixtures were abandoned for the convenience of the art store and quick production.

The pure magic and beauty of buon fresco struck home the moment iLia applied the golden ochre-yellow halo against the blue sky. Although I knew it was simply ground up marble and minerals, essentially paint on stone, it looked like a back-lit display, a stained glass window. “Antiqued” later, it inhabited the wall as if indeed, more wall had existed centuries ago, with only the three fragments remaining. This effect will become more so with age.

When archaeologists of the future dig Hollywood out of the earthquake rubble, I’d like to be a fly on the wall as they attempt to figure out how and when Italian fresco artists inhabited Los Angeles.

by Shelley Dale

about the Artist:

iLia Anossov (fresco) is one of the few artists in the world considered a master of the art of fresco painting. His fresco work includes paintings, installations, objects, sculptures and his signature fresco “stacks”.

iLia has been widely exhibited in Russia, Europe and the United States including 7 museum exhibitions and over 50 solo and group exhibitions. Commissions include large-scale fresco installations and murals in private homes and public areas. His internationally featured Malibu Fresco project appeared on the covers of premier magazines including Architectural Digest (AD) USA/Germany/Italy, House & Garden UK.

iLia’s creative mind and artistic excellence has been in high demand for prestigious events and productions. One of his most notable commissions was the design and creation of the interior décor of the 76th Annual Academy Awards® Governor’s Ball. Over 27,000 sq. feet was hand painted in t”rompe l’oeil frescoes”. iLia’s work has graced such events as the 73rd Academy Awards® Governor’s Ball, 9th Annual SAG Awards Governor’s Ball, 50th Annual Emmy Awards, 11th Nickelodeon Kids Choice Awards and many others.